Back in 1999 Tory Bilski was sitting in her office at Yale University, where she edits journals for political economists. Feeling uninspired, she was surfing the web when she unexpectedly came across a pixelated picture of an Icelandic horse – and fell in love!

Back in 1999 Tory Bilski was sitting in her office at Yale University, where she edits journals for political economists. Feeling uninspired, she was surfing the web when she unexpectedly came across a pixelated picture of an Icelandic horse – and fell in love!

I was nothing short of obsessed, a girl again, smitten. It was a well-muscled horse with a noble head, a compact body, flaring nostrils, and a Fabian black mane swept back from the wind. I knew it was a stallion; he had that tough-guy look to him. It was a horse that I felt some past kinship with, a memory of, a familiarity of place and time (I know, I know . . .). Usually I don’t believe in past lives until my third glass of wine, but there I was, midday and procrastinating at work, staring at this dark horse that stared right back at me. We reconnected. It had been centuries. So the dream began. This place: Iceland; that horse: Icelandic.

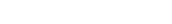

(From Wild Horses of the Summer Sun, 2019, by Tory Bilski.)

A few years later, Tory had become known as “the woman who goes to Iceland to ride horses” in her hometown. For more than a decade, she travelled to Iceland every year with her friends to go on horse treks in the Icelandic countryside, a tradition which became like therapy to her. Last spring, she released her memoir Wild Horses of the Summer Sun, a heart-warming and often hilarious account of her years in Iceland, her love for Icelandic horses and the country that makes them such a special breed.

A few years later, Tory had become known as “the woman who goes to Iceland to ride horses” in her hometown. For more than a decade, she travelled to Iceland every year with her friends to go on horse treks in the Icelandic countryside, a tradition which became like therapy to her. Last spring, she released her memoir Wild Horses of the Summer Sun, a heart-warming and often hilarious account of her years in Iceland, her love for Icelandic horses and the country that makes them such a special breed.

When you saw that picture, you had just gotten back to riding after 20-30 years – on Thoroughbreds – but felt unfulfilled. Why was that?

“I went to a local stable where I would walk, trot and canter inside an arena, but I kept feeling that I wasn’t getting anywhere and that I needed something more.”

And then you tried riding an Icelandic horse for the first time, on a three-hour trek in Vermont. How was it different?

“I felt comfortable in the saddle and connected to that horse. It fit me. I discovered that I really liked horse treks—I didn’t want to ride around in circles. It’s fine to take lessons but I needed that trekking experience. When you’re trekking, you’re learning in an intuitive way because you’re on that horse for so long.”

Could you describe your first experience of riding in Iceland?

“My first time in Iceland I signed up with an equitour company at a farm and it was basically farmers who let people come ride with them, but it wasn’t training. You didn’t get the sense that they were watching you. You were kind of on your own, which has some benefits to it, but it was old school riding. I sense that Hólar training is the new school approach.”

Speaking of “the new school”: From 2004 to 2015 you were part of an exclusive group of women who were invited to go riding at Þingeyrar in Northwest Iceland. The farm was run by horse breeder Helga Thoroddsen, who at the time was also instructor in Equine Studies at Hólar University College. What was so special about Hólar and riding with Helga?

“Hólar is like a horse Mecca to us Americans. It’s very hard for people to get into Hólar and it has a reputation for being a great training programme because it’s science based. At Þingeyrar we took lessons at the end of the day and there were often Hólar interns helping us out on the trail for the summer and giving instructions which was good practice for them.”

What is the difference between riding Icelandic horses in the US and in Iceland?

“Where I live in the Northeast it’s very forested with big heavy trees. When I’m riding on a trail neither I nor the horse can see behind the corner and I have this feeling that something might come out at me. There was a bear sighted just down the block in the suburban town where I live. In Iceland there are no predatory animals which gives you an additional sense of freedom.”

What is so special about the Icelandic horse?

“You can go up to an Icelandic horse in the field and it’s friendly and curious. In the barn when saddling up it remains calm. You never have to tie it so that it will stay still for you. Then you get on the horse and the minute you head out it becomes alert and energetic and willing. It’s like it’s saying: ‘Ok lady, I’m taking you for this ride. I’ve got it. Just let me go.’ The horse is part of its environment and you sense the difference. It’s the way they’re bred and brought up, semi-feral. They’re let out into mountains for months at a time to forage on their own. They’re not coddled like pets. It does something to their brains which makes them smart – they’re allowed to be horses.”

Can anyone ride an Icelandic horse?

“Icelandic horses have a very willing spirit. All the gaits make them easy to ride from A to B in a safe way. Then you realise that it’s complicated to have these gaits and that there’s a lot to learn, so much that I will never learn everything in my lifetime. But it’s ok because I can get a lot out of it without being an expert horse woman.”

You speak of you and your friends who ride at Þingeyrar as “converts”. Could you explain?

“We all have our own story of riding big horses and having a hard time with it because all of us went back to riding in our middle age – and one of the women went back at 59! Each friend had their own way of discovering the Icelandic horse and then they never went back to other horses. I have a history with Thoroughbreds, big muscular horses, but when I started riding Icelandics, that was it, we were converts! Now I feel nervous on other horses, actually.”

You write that your favourite gait is canter. Why is that?

“A smooth tölt is great but when I was a horse-crazy young girl I just wanted to canter in the meadows; but then it ended up being the tussocks of Iceland! It feels really smooth to me and I rarely lose my seat. I’d lose my seat a lot on a big horse so I just never wanted to canter them a lot. When I tried flying pace on an Icelandic it wasn’t on purpose. I didn’t know what was going on. It doesn’t feel like anything else. It feels like flying.”

How is riding in Iceland therapeutic to you?

“When you’re trekking, everything in your mind is really centered on the immediacy of the moment: the path in front of you, the gait of your horse, your seat. But you’re not really thinking about yourself, you’re totally immersed in the ride. When you are that involved in a moment it brings a sense of peace and harmony. In a good way, you lose yourself by being in the moment. Others feel this way when they’re surfing, or skiing up in the mountains. Also, the sense of being outdoors. There’s birdsong and dogs barking and all this orchestra of sound and the northern part of Iceland calls to me. There’s a desolate beauty in the vastness and in the summer there’s gorgeous light.”

What do you take away from the experience of riding in Iceland?

“It’s just amazing being with the horse in its natural environment and being surrounded by horses. It brings a sense of freedom – which is the closest word to describe what I and everyone else was experiencing. And in this group of women we have made friendships that are going to stay with us for a long time after we come home.”

Wild Horses of the Summer Sun – A Memoir of Iceland by Tory Bilski was published by Pegasus Books (New York) in May 2019, and by Murdoch Books in the UK, Australia, and New Zealand. It will also be published and translated in Germany and the Netherlands. It’s available on Amazon, Barnes & Nobles, Waterstones, Foyles, Penninn Eymundsson, and bookstores everywhere.

Text: Eygló Svala Arnarsdóttir. Photos courtesy of Tory Bilski.

-1.jpg)